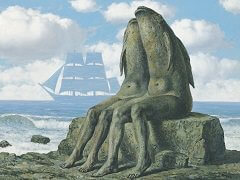

Seducer, 1953 by Rene Magritte

Certainly no one would mistake The Seducer, painted in 1953, for an ordinary landscape. A ship floats alone on an ideal sea, surrounded by one of Magritte's favorite motifs, clouds. Think of the idiom in English today, cloud nine. One has no indication of time, place, or the weather, no hint of sunlight or rain beyond the blue sky and stereotypical cumulus clouds. The sailing ship-of a kind once built for long ocean voyages-belongs to some unspecified past as remote and idealized as a manipulated dream world.

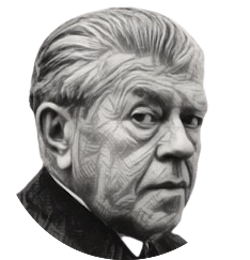

Magritte probably had little personal experience of the sea anyway. He grew up almost dead center in Belgium, in a small town southwest of Brussels, where the plains of Waterloo start to give way to the hilly terrain of Mons. He returned from Paris to Brussels in 1930, pretty much for good. One could call him the perfect bourgeois, a role he loved to play in his art, although indications of an actual city appear as rarely in his art as anything else concrete.

Even back in the time of sailing ships, Belgium never rivaled its neighbors as a naval power. The Dutch, after breaking free of Spain, celebrated their ports in Baroque art, but not the Flemish. If Magritte ever felt the call of the sea, it had to mean a call within.

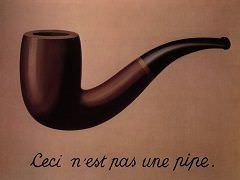

Most obviously unlike a seascape, Magritte has done something odd indeed to the ship: he has replaced its shape with an extension of the water. Surrealism celebrated just such illogical, uncanny juxtapositions. Breton liked to cite a writer calling himself Comte de Lautréamont, who in 1868 asked for an image "as beautiful as the chance meeting on a dissecting table of a sewing machine and an umbrella." One can think of the ship's transformation as a cut-and-paste job, and Surrealism has its roots, like pretty much all modern art, in Cubist collage.

If that leaves only a dream, the painting's title, The Seducer, also suggests uncensored fantasy, and Magritte himself spoke of painting not just real objects, as in a still life, but "real desires." Whoever is carrying out a seduction, no one is restraining his transgression. In French, seduction has connotations of pleasure and magic, and some critics have termed his art "magic realism"-and a precursor of the movement in America that spawned Philip Evergood and George Tooker. However, the seducer does not clearly appear. The pleasure seeker could be riding on the ship, painting it, or looking at it in the museum now. So could the one seduced-perhaps Magritte himself seduced by his own art.